A Message from 300 B.C.

All the children who are held and loved will know how to love others… Spread these virtues in the world. Nothing more need be done. — Mencius

Those tender and hopeful words were voiced by a man born into an age of brutal warfare, when massive armies were on the march, violently conquering smaller kingdoms. Mencius (known as Mengzi in China) lived around 300 B.C., a period in Chinese history known as the age of the “Warring States.”

Yet Mencius, regarded as China’s second greatest philosopher, after Confucius, was an optimist—and his observations about human nature have been passed down through the ages.

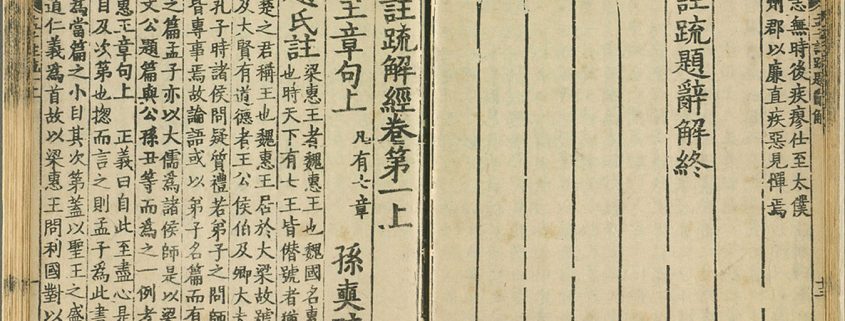

Mencius’ philosophical contributions were vast, although scholars say he mentioned this concept of the goodness of human beings only three times in his writing. Yet that’s the idea he is best remembered for.

How did the old sage come to express such optimism? Perhaps he was just born with a kind heart and the gift of seeing the best in people. Maybe he grew wise through his studies, and the influence of his mother. Mother Meng worked as a weaver, and she herself is revered in China.

An old saying goes, “Mother Meng moved three times.” She did, until she found a place that would be a good environment for her son—a home next door to a school. This search gave rise to her reputation as a caring mother who was deeply devoted to her son’s education.

When the young Mencius skipped school one day, not only did his mother give him a stern talking to, but legend has it that she picked up a pair of scissors and cut through the threads of her own weaving. That, she told the young boy, is what will happen to your own prospects if you continue to be lazy.

Mencius got serious about his studies, enough to become a great sage whose work—and hopeful point of view–has made its way through the centuries. He argued that benevolence was more rational than selfish behavior because of its capacity to promote social harmony. Even rulers, he believed, could treat people humanely and with love.

The old optimist, in fact, had a lot of wise things to say, observations that apply as much today as they did then. “Friendship is one mind in two bodies.” Or, “The great man is one who does not lose his child’s heart.”

Mencius liked to make his point about human nature by posing this question: What would happen if a group of villagers saw a child fall down a well?

Of, course, everyone around would rush to help, he said, and even those who didn’t pitch in would still care about the fate of that child. He argued that because people loved their own families, they could love other people’s family members, as well, and every human was capable of extending love beyond family.

Today, some 2000 years later, a growing body of scientific inquiry is underscoring with research what the old philosopher felt in his bones: that people are born with a capacity for compassion and empathy. That children who are held and loved grow into adults who can love others. That a quality of inner goodness will emerge when people experience love. But, cautioned Mencius, in order for good qualities to prevail in people, they must be cultivated.

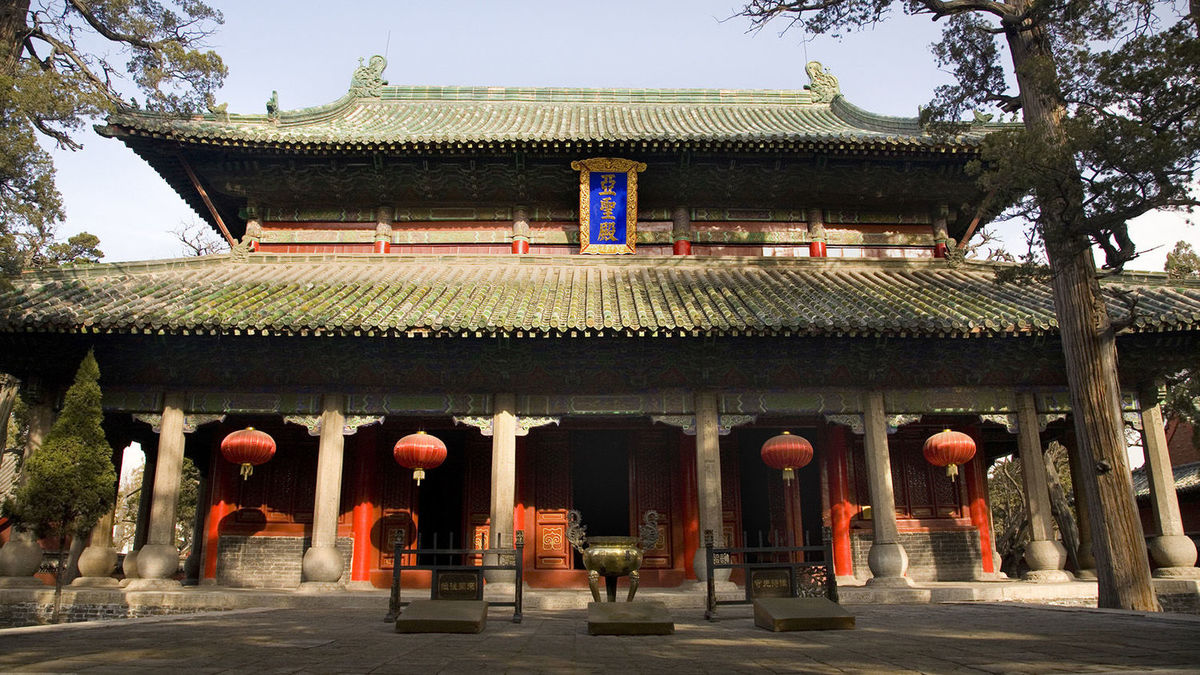

The Mencius Temple today